By Jackie Jonas

Years ago I met a woman named Marva who had converted to Judaism in her twenties. Marva told me that the Orthodox Rabbi who supervised her conversion as a Black woman asked “What, you don’t have enough trouble?” That was the response of one of the rabbis on the Bet Din for my conversion as well. My response was much like Marva’s: They are going to see me coming anyway, I might as well do what I want. To the more serious questions during that conversion process, I responded by talking about my upbringing in a family of gospel singers and preachers. I told them about my paternal grandfather, who was an apostolic bishop, and my mother and aunt who were gospel singers. I told them about listening to Black preachers thunder the Word out of the pulpit, dwelling in the Old Testament with its stories of struggle and redemption. I explained that I was always told to seek my own path, and that my grandfather, Bishop Wiley, had only one requirement of any of his grandchildren: that we find a path to God and stick with it. My mother, too, required that her children be good people, but she did not insist that we follow her path.

When my husband and I married, I was clear that we needed to raise any children that we had in a religious home. I was not comfortable with raising them in a Christian home because by that time I was no longer a practicing Christian, and my husband was Jewish. So I spent ten years studying Judaism and creating a Jewish home. When our daughter came to us 6 years into the marriage, we raised her as a Jewish child, sending her to Hebrew school and Jewish camps. She became a Bat Mitzvah, was confirmed, spent every summer from the time she was 10 at a Reform Jewish camp, eventually becoming a counselor there. And she still thinks of herself as Jewish. But like me, she thinks of herself as a Black woman first.

I began my journey when my husband and I joined Chicago Sinai congregation. Chicago Sinai is a classical Reform congregation that at the time met on the South Side of the city. From the beginning I felt welcome there. While there were no other Black congregants at the time, I never felt uncomfortable or unwelcome. My daughter came to us while we were members there, and Rabbi Howard Berman officiated at her naming ceremony which was held in the home of a fellow congregant. We left Chicago Sinai when we moved to my husband’s hometown of Pittsburgh, and my experience of being Black and Jewish changed. I have been officially Jewish for close to thirty years now but have lived a Jewish life longer than that. Over the years since leaving Chicago Sinai I attended synagogue regularly, taught in the religious schools in two temples in Pittsburgh, received an award for excellence in Jewish education, chanted the Haftorah blessings at the High Holidays, and until joining my current congregation 5 years ago, I have never been in a Jewish space where I was not asked to justify my presence. It is the paradox that Non-White Jews in North America face. We are part of the community, but we don’t look the part. When we travel to other parts of the world, we see Jews of every hue, but here in North America, we are surrounded by Jews of European descent. Here we conflate Jewishness and Whiteness. And so Jews of color are called upon to navigate our co-religionists’ discomfort. This is not something I find difficult to do, but I will tell you it can get tiring.

Being Black and having chosen Judaism as my religion has led to some interesting conversations and issues. When the recent BLM protests began, I watched my white co-congregants struggle with where to place themselves in that struggle. I found myself retreating to my Black support group because as I said thirty years ago, they will see me coming. This has been something of a blessing. I have been able to keep my spiritual practice as a personal part of my life. Being a visible minority, that is a relief. People tend to be hyper aware of us in public spaces, so it is nice to have some part of myself that I get to decide when and if to disclose and put up for discussion. When my husband and I relocated to Philadelphia five years ago, we sought a congregation that was accepting of diversity. We found that in Mishkan Shalom. It was the first time I had walked into a Jewish space in years and not gotten the “look.” It was refreshing not to have people just flat out ask me how I came to be Jewish sometimes even before they asked my name. When I talk about my Judaism, I talk about being spiritually Jewish and culturally Black. That is a marvelous combination and one that Black folks have no problem relating to. We spend our lives learning to be culturally bilingual. And now as a mother and grandmother, I am watching my daughter and granddaughter learn that as well. I hope that my daughter’s Jewish upbringing will help her navigate the world with a strong sense of herself and her place.

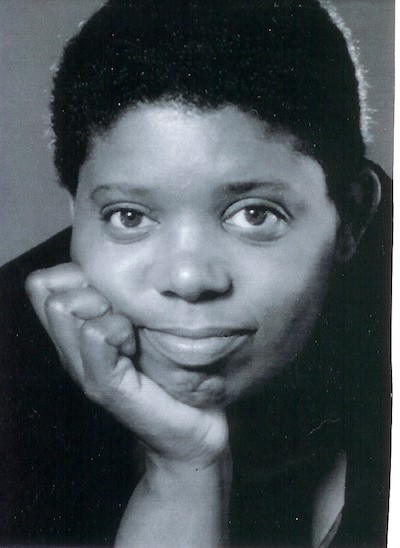

Jackie Jonas is a storyteller, actress, former IT professional and a retired teacher. She was a 2005 recipient of the Grinspoon-Steinhardt award for excellence in Jewish Education. She is currently a member of Grounded Theatre Company and lives with her husband in Mt. Airy.